Aggregation of Services Pattern with Elixir

Thank you my friends Anton, Jan, and Thales for the awesome revision. ❤❤❤

Hello, everyone! I’m here to talk about an architectural pattern that I have experienced working with Elixir for many companies so far. Here, we’ll discuss how to do your software project with low cost and high enjoyment. We’ll see how Elixir libraries, umbrella apps, protocols and behaviours can help you with that. Enough of the introduction; let’s start defining the problem.

The Problem

A system that contains an aggregation of services offers functionalities that can be done by multiple service providers. The biggest problem of this kind of software is how to manage the large codebase that it can generate given all the code we need to address each service provider’s peculiarities in a homogeneous form to the rest of the application and their customers.

The most common symptoms of a problematic design show up when we add new integrations: they are way slower to build than the first and break old integrations.

When developers know that it is just a first integration from many, they will be automatically more careful when writing their code and organising their modules to accommodate future integrations. But at this point, it’s challenging to know all the unknowns of future integrations, then some pragmatic assumptions and decisions are needed. Otherwise, they can fall into a pitfall of over-engineering.

Sometimes neither the developers nor the product managers know the future of the software. In those cases, developers tailor the solution strictly to work with a single service provider. Later, when a new provider comes, the first need to keep operant while the second provider often needs to seamlessly fit the same service interface. So, developers might need to do a total rework of the first iteration because the system was tailored to run with a single service provider, not many.

Here, I’ll try to give you suggestions to organise your Elixir project. The advice here can be helpful even if you don’t know your software’s future. Please, don’t assume this is the definitive guide that fits every context and team. Remember, every team and project is different. Pick the guidelines that have the potential to help your organisation.

CentralSource Example

The aggregator of services software can be more common than you might think. It can be the most essential product service. Or a particular part of a bigger system. Or, it can also be accidental. The customer’s choice can be explicit or implicit by the product through complex routing or decision rules mechanism.

Here are some examples. Let’s say you want to build an application that looks up all the food delivery apps and find the best deal for the customer. Or you need to provide multiple payments options for your customer in your e-commerce. Or maybe you want to build a website that centralises users’ game profile by collecting their achievements through many game platforms. All these applications have a similar problem of managing a set of features through many service suppliers. Sometimes it is their main selling point. Sometimes it is just a particular part of the system.

I think it’s beneficial to build up an example along this article’s journey. It will be a disruptive new application that I thought of after 30 seconds of an exhausting brainstorming session with myself. I called this application CentralSource. This app allows users to manage their code repositories through many source control providers, like GitRub, BitPocket, GitTab and many others that can come.

The overall idea

When we’re building an aggregator of services, we start by integrating one service provider. The first one usually is fast to integrate. Usually, the problem begins when we add the next. The naive first implementation would put all the service provider needs in a single application module. It can degrade fast, and structured growth feels necessary.

Why not start with a naive implementation? Let’s say we want to display all repositories of a given user. Here’s an Elixir example for our innovative CentralSource:

# lib/central_source/source_suppliers.ex

defmodule CentralSource.SourceSuppliers do

def list_repos(owner) do

{:ok, response} = HTTPClient.get("https://api.gitrub.com/repos/#{owner}")

Jason.parse!(response.body)

end

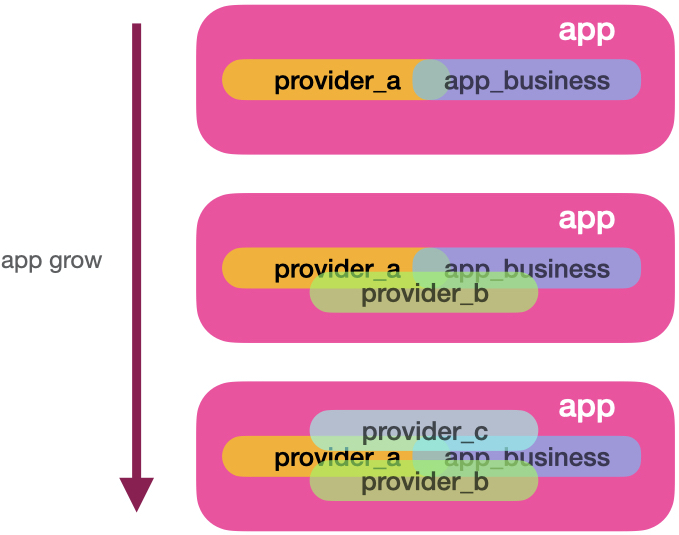

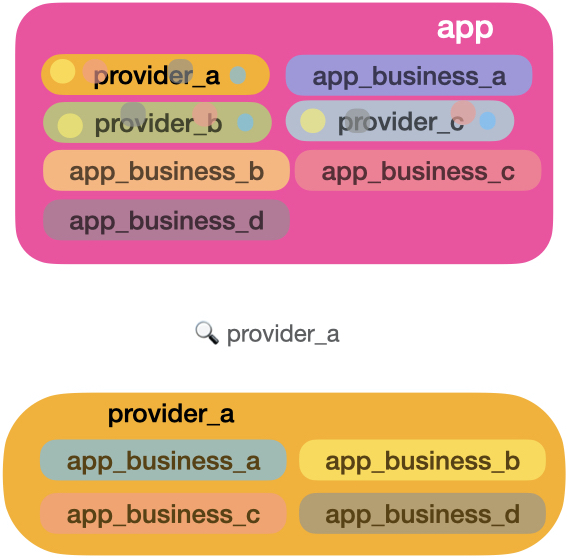

endThis works pretty well for one service provider and one function. But remember, we also need to integrate BitPocket and GitTab. If we put it all here, all service providers’ peculiarities will start to mix with each other. It can be worse. The providers’ code can mix with your application business. The image below illustrates the growing problem of keeping everything in a single module:

It’s hard to visualise when one provider logic ends, and another starts. The complexity of functions here can be immense since we might need many function clauses, cases and ifs to accommodate each service provider necessity. One benefit that might show up here is a smaller number of code lines since they might reuse similar functions. However, reusability is a double-edged sword because every change impacts old providers and increases the module complexity.

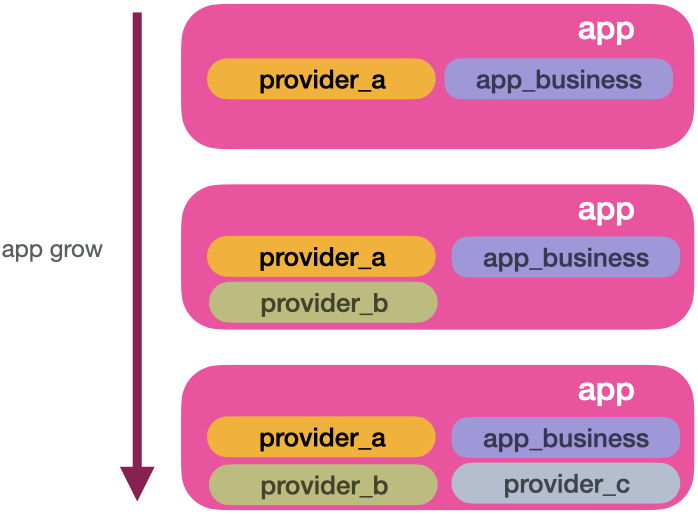

We can’t always remove complexity, but we can organise it. As a solution for that, we can split up each service provider connection to its own module and folder:

Here we can see structured growth. You might end up duplicating some code. But the independence pays off. Let’s say provider_a needs an HTTP for a REST API client, while provider_b uses a gRPC and provider_c RabbitMQ. Since each provider grows independently, these concepts will not overlap each other. You also open room for experiment. Maybe a developer found a new HTTP client that looks neat. It can be a useful test in a single provider before pushing the shiny new library to the others. It’s up to you to find the balance of reusability. For example, you might want a standard way of measuring the provider HTTP clients performance. In that case, it’s good to create reusable tools that you can plug in the provider’s modules. Tesla.Middleware is an excellent example of reusable and pluggable functionality independent of context.

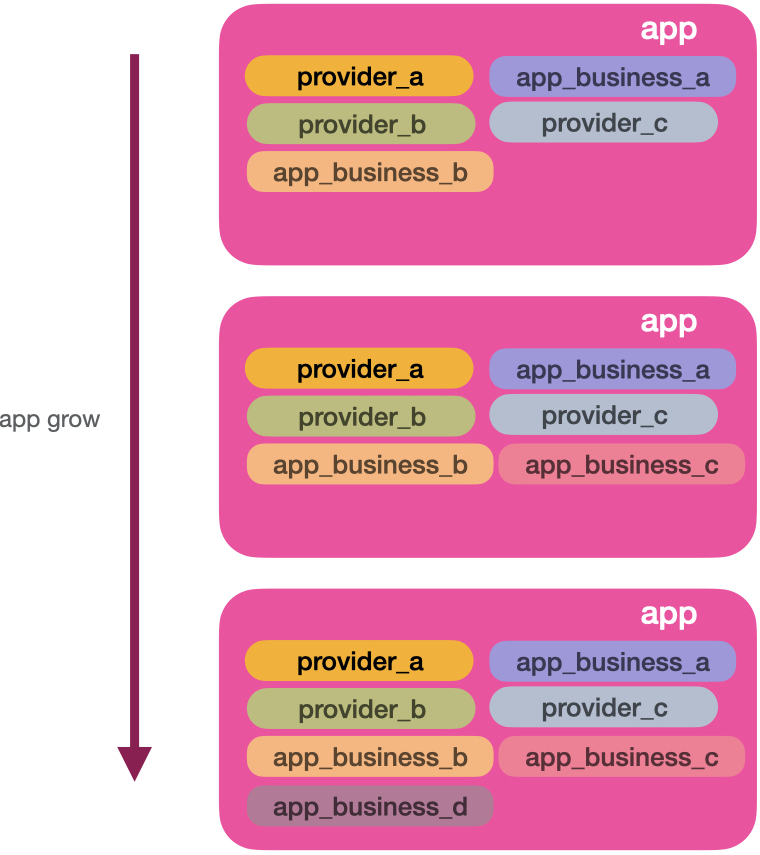

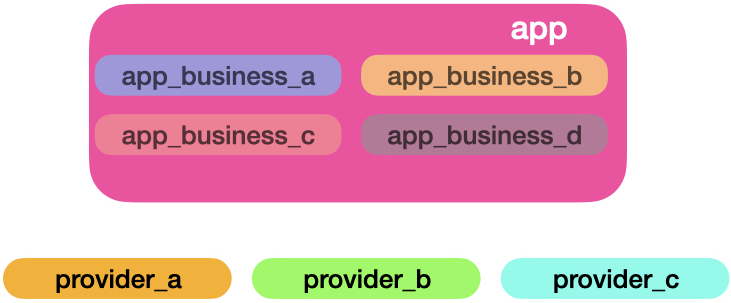

Most of the time, this kind of organisation is enough. However, your application’s internal business rules might grow over time. For example, the CentralSource application started to read and manage repositories from many source control services. After a few months, it has absorbed users and organisations management, access control, social network, stories, backup services, and much more. We can see the visualisation of the growth in the image below:

When the application business code starts to increase, the providers’ modules might look misplaced. Another effect that often happens is application business data tainting the providers’ module space. For example, given the same data source, app_business_a needs a list in A struct shape, while app_business_b needs the same contents in a B shape. This rule has a high probability of being replicated in all providers’ modules. The image below illustrates the situation:

The colours of each application business are invading the provider’s territory. The opposite can also happen. The specifics of each provider can taint the application modules. One way to prevent that, we can push the providers’ code away from your core application.

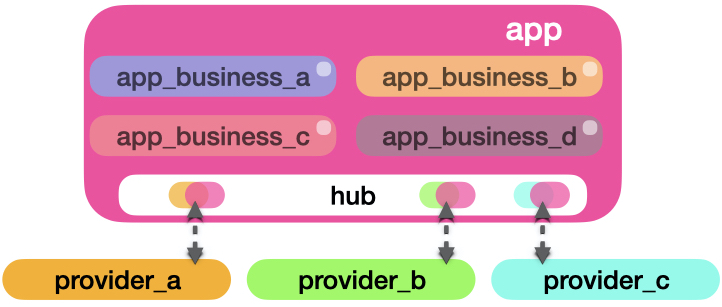

This illustration is heavily inspired by Hexagonal Architecture. Basically, all the providers context modules are adapters for application core do their business. Here, the independence of each provider module is further encouraged. Here’s an important matter, each provider context modules being completely independent of the app core. A library mindset. No references to application core modules, data types, structs or even configuration. Moving the provider module to be a mix dependency shouldn’t be too hard. But of course, at the same time, we should develop the provider’s module to be useful to the application core. But how does the application core access the providers? Look at the next graph:

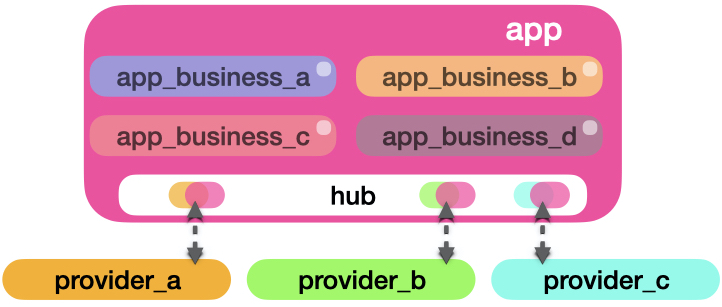

The image above illustrates the Aggregation of Services Pattern (AoS). The “hub” context will live on the application core and serve as a mediator between the application core and providers. It will provide interfaces and data types that the app business modules can rely on. If we plug more providers, we should not significantly change the rest of the application business. The emphasis on significantly here is essential. Adding new service providers can often require changes to the rest of the application, especially when AoS is a new concept in your system. Using this approach doesn’t mean also you will write less code. It’s the opposite. You might end up writing more code to make the boundary clear between your app and the rest of the moving parts. Here’s just a way to have structured growth that is easy to reason about.

You don’t need to call the mediator module “hub”. I have seen this be called “Providers”, “Connectors”, “Link”, “Suppliers”, “Externals”, “Gate”. I suggest you find a name that connects with their business type since you can end up having multiple hub contexts in your application. For example, for the CentralRepo application, the “hub” module will be called “SourceSuppliers”.

Now that we have the same picture in our head of how Aggregation of Services Pattern looks and works, let’s see the implementation details with Elixir.

The directory structure

A good project directory structure can help you define better boundaries on your system and keep each integration client independent as possible. We’ll explore many ways you can organise your project using AoS. We’ll go from simple Elixir applications to Umbrella ones.

Just a lib directory

This is one of my favourite ways since it’s effortless to start and manipulate, and it is flexible to allow us to break the rules when necessary. The flexibility is also the downside. We need to be vigilant on code reviews to prevent our commitment to the pattern from breaking and getting out of control. Let’s see how it works.

When you use the default’ mix new [project_name]’ command, it creates a ‘/lib’ folder where you can put your code. Inside that folder, there’s also a file with your project’s name. You can create a folder with your application name. There is where your application core business will live. For the integration clients, you can generate sibling folders of your application. See:

.

├── lib

│ ├── bit_pocket

│ ├── central_source

│ ├── git_rub

│ └── git_tab

└── testIt is not a new idea in the Elixir community. For example, If you start a new Phoenix project, the same structure also shows up. Phoenix creates two folders by default. One is project_name, where your application core logic lives. And the other is project_name_web, a way where your project is exposed to users. The web is also a matter of infrastructure, like provider integration clients. If we end up with a command-line interface, we could create another directory called project_name_cli in your lib, for example.

The simplicity here is good. However, it doesn’t enforce any rules. For example, a call from the GitRub module to any function in CentralRepo goes against the pattern. But we don’t have any warning or compilation failure. It’s up to the developers to keep consistent. Personally, this is my favourite way because sometimes it’s good to have an exit door to break the pattern. However, if you want to go strict, take a look at Boundary from Sasa Juric and also the other solutions here in the article.

Single repo managing external dependencies

Maybe your team isn’t happy enough with just a directory boundary and want more. You can treat the provider folder as a separated Elixir project and reference it as a dependency in your project mix file. At the same time, this brings compile-time guarantees. It also gets an extra job to set up and configure your ci.

First, you’ll have to create a folder separated from your lib. The name of the folder it’s up to you, but if you want a name, here’s one /vendor. Then, you create a new Elixir project for every new service client with mix new [name-of-the-client].Your application can reference it by adding to the list of the dependencies using the path option.

├── lib

│ └── central_source

├── test

└── vendor

├── bit_pocket

│ ├── lib

│ └── test

├── git_rub

│ ├── lib

│ └── test

└── git_tab

├── lib

└── test defp deps do

[

{:git_rub, path: "vendor/git_rub"},

{:git_tab, path: "vendor/git_tab"},

{:bit_pocket, path: "vendor/bit_pocket"}

]

endIt is a self-contained library inside of your codebase. It means it has its own mix file and test suite. So you might need to write yourself the quality of life scripts to build and test your dependencies in a few commands.

The good thing about this approach is the compilation boundary that creates between your clients and the application. The clients can’t access the application’s modules without listing them in their mix dependencies list. But the cost is the manual scripting and configuration that developers need to write by themselves and the amount of boilerplate code that comes from project generators.

Depending on your needs, this solution can be overkill. But if you really want to push it even further, instead of storing it in a single repository, you can put the clients on external repositories. I don’t recommend that for fast pacing development, but maybe your clients have grown so much and can be useful for more people; it might make sense turn it into an open-source project.

Umbrella projects

Elixir Umbrella projects offer you convenient tooling to manage multiple applications that need to run together in a single repository. In the umbrella projects universe, application or app is any Elixir project with or without supervision tree. Each app can be a service client with its own mix file to describe its dependencies.

If you read the previous section, both approaches are pretty similar. The difference is umbrella gives you productive tooling in exchange for a little bit more coupling. The coupling comes from the fact that all the dependencies and configuration are shared between all apps. While the productivity comes from the mix, it gives you all the tools to compile and test your apps with a single command.

The umbrella project enforces the boundary by emitting warnings if some app references another without explicitly listing it in its own mix dependencies. Then, It’s up to you to make the warnings become errors with mix compile --warning-as-errors.

.

├── apps

│ ├── bit_pocket

│ │ ├── lib

│ │ └── test

│ ├── central_source

│ │ ├── lib

│ │ └── test

│ ├── git_rub

│ │ ├── lib

│ │ └── test

│ └── git_tab

│ ├── lib

│ └── test

└── config defp deps do

[

{:git_rub, in_umbrella: true},

{:git_tab, in_umbrella: true}

{:bit_pocket, in_umbrella: true}

]

endI don’t have too much experience manually managing external Elixir dependencies inside of a single repository. Given the conveniences and resources you can find about umbrella projects, I would definitely choose umbrella projects rather than manual management.

Big project

Our projects’ directories and files live on a limitation of today’s operating systems’ hierarchical tree structure. Sometimes you might end with many directories inside your apps or lib folder. For some people, it can feel overwhelming and unorganised, so more structuring might be needed. But any solution will end up with some tradeoffs to make.

If you are just using a lib folder, you have all the flexibility to create any folder structure you want to categorise your service clients. Just be careful. You don’t need to reflect the folder structure in your module’s namespace. The name of your client service it’s good to match their folder name but doesn’t need to be consistent with any parent structure you might have. For example:

.

├── lib

│ ├── central_source

│ └── source_suppliers

│ ├── bit_pocket

│ ├── git_rub

│ └── git_tab# preferred

defmodule BitPocket do

# okayish

defmodule SourceSuppliers.BitPocket doThe source_suppliers directory there is just for operating system directory organisation. Not necessary means that each provider wrapper needs to live under the same namespace. Doing this can save you some unnecessary diff when news directories restructuring happens and enforces the idea that each client is a self-contained project.

In the umbrella projects world, you don’t have too much room for restructuring because it only allows a single root directory for your apps. You might want to organise by creating an app for your AoS and moving all their clients’ dependencies to its directory. Then, the aggregator app will work like the “just a lib directory” approach. This way, we lose the compilation boundary enforcement inside of the aggregator. Still, at the same time, we offer a layer of isolation expressing that service clients are dependencies of the aggregator app.

I don’t have hard feelings about having a directory with many applications inside, but I miss different directory visualisation methods. I would like to visualise the apps grouped by user-defined tags. I would like also having a visualisation tool that shows the dependencies graph of the apps. I feel a little bit sad with the folder structuring we end up with because of our current tooling limitations.

We discussed some options on how you can organise your Aggregation of Services applications in Elixir. You can pick your favourite one. Your directory choice doesn’t matter for the next topics. In runtime, Elixir modules live on computer memory, so it doesn’t matter which directory they live. Let’s now talk about code!

Dispatch with Elixir Behaviours

When building an AoS, it’s popular to have a central module where you can call any external service. The target service is decided on runtime through a decision-making code that checks configuration or customer request parameters. Here, we’ll implement this dispatcher using Elixir Behaviours following the hub of clients pattern.

Let’s use CentralSource as an example. Let’s say we want to list all repositories across different service providers. Using the client and hub approach, we should create first our isolated clients that don’t care about our CentralSource application:

# lib/git_rub/git_rub.ex

defmodule GitRub do

alias GitRub.{HTTP, Repo}

@spec list_repos(username :: String.t()) :: {:ok, [Repo.t()]} | {:error, atom}

def list_repos(username) when is_binary(username) do

with {:ok, json_repos} <- HTTP.get_repos(username) do

{:ok, Enum.map(json_repos, &Repo.from_json/1)

end

end

end# lib/bit_pocket/bit_pocket.ex

defmodule BitPocket do

alias BitPocket.{FTP, Pocket}

@spec entries(username :: String.t()) :: {:ok, [Pocket.t()]} | {:error, atom}

def entries(username) when is_binary(username) do

with {:ok, xml_entries} <- FTP.download_entries_meta(username) do

{:ok, Enum.map(xml_entries, &Pocket.from_xml/1)

end

end

end# lib/git_tab/git_tab.ex

defmodule GitTab do

alias GitTab.{HTTP, Repo}

@spec get_repos(username :: String.t(), limit :: pos_integer) :: {:ok, [Repo.t()]} | {:error, atom}

def get_repos(username, limit \\ 50) when is_binary(username) and is_integer(limit) and limit > 0 do

with {:ok, json_repos} <- HTTP.get_repos(username) do

{:ok, Enum.map(json_repos, &Repo.from_json/1)

end

end

endYou can see here, each client looks pretty similar but with a few differences. While GitTab and GitRub use HTTP JSON APIs, BitPocket needs to download some FTP server file. BitPocket and GitRub have similar function arguments, but, GitTab requires a second argument called limit. These clients should have accurate naming and not hide the capabilities from services they are wrapping. BitPocket calls their repositories “Pockets”, GitTab requires the limit option. All that inconsistency it’s okay here. The benefit of doing it is when reading project codebase doing some other task, you can understand the client functions without having to jump to the service official docs all the time. Also, suppose you need to debug and fix these clients one day. In that case, it will be easier to find what you are looking for in their official docs because all the functions, arguments, and data types are reflecting their original services idiom.

Now that we defined our borders with external services. Let’s focus on our application core. We need to create a hub module that will serve other application modules. You can think that this “hub” is a context module (from Phoenix contexts), an entry point. We’ll name it “SourceSuppliers”.

# lib/central_source/source_suppliers/source_suppliers.ex

defmodule CentralSource.SourceSuppliers do

alias CentralSource.Accounts.User

alias CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.Repo

@spec get_user_repos(User.t()) :: {:ok, [Repo.t()]} | {:error, atom}

def get_user_repos(user = %User{}) do

end

endHere we defined the entry point to get all repositories across many services of a given user. But how? Each client works differently! How to return a uniform and standard response? We need a translator that takes each client’s inconsistency and transform it into consistent data that the rest of our app requires. Here is where Elixir behaviours can help us!

We can define an interface using the @callback directive. Each service client will have a translation implementation following the interface, so the rest of the codebase can have an easy life relying on it.

# lib/central_source/source_suppliers/source_suppliers.ex

defmodule CentralSource.SourceSuppliers do

alias CentralSource.Accounts.User

alias CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.Repo

@doc """

Invoked to fetch users repositories given their username account.

"""

@callback get_user_repos(username :: String.t()) :: {:ok, [Repo.t()]} | {:error, atom}

# ...Here I put the callback in the same module context just for the example convenience. A single organised file approach is easy to navigate, but you might want to break down the interface into a different file. Now it’s time to implement the translators:

# lib/central_source/source_suppliers/git_rub.ex

defmodule CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.GitRub do

alias CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.Repo

@behaviour CentralSource.SourceSuppliers

@impl true

def get_user_repos(username) do

with {:ok, gitrub_repos} <- GitRub.list_repos(username) do

repos =

for github_repo <- gitrub_repos do

%Repo{

name: github_repo.repo_name,

owner: github_repo.user,

url: github_repo.repo_url,

kind: :gitrub,

forks_count: github_repo.forks,

favorite_count: github_repo.stars,

followers_count: github_repo.watchers

}

end

end

end

end# lib/central_source/source_suppliers/bit_pocket.ex

defmodule CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.BitPocket do

alias CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.Repo

@behaviour CentralSource.SourceSuppliers

@impl true

def get_user_repos(username) do

with {:ok, bitpocket_repos} <- BitPocket.entries(username) do

repos =

for bitpocket_repo <- bitpocket_repos do

%Repo{

name: bitpocket_repo.name,

owner: bitpocket_repo.author,

url: BitPocket.Repo.url(bitpocket_repo),

kind: :bitpocket,

forks_count: :unknown,

favorite_count: :unknown,

followers_count: :unknown

}

end

end

end

end# lib/central_source/source_suppliers/git_tab.ex

defmodule CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.GitTab do

alias CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.Repo

@behaviour CentralSource.SourceSuppliers

@impl true

def get_user_repos(username) do

limit = 100

with {:ok, gittab_repos} <- GitTab.get_repos(username, limit) do

repos =

for gittab_repo <- gittab_repos do

%Repo{

name: gittab_repo.name,

owner: gittab_repo.owner,

url: gittab.url,

kind: :gittab,

forks_count: length(gittab.clones),

favorite_count: gittab.likes,

followers_count: gittab.followers

}

end

end

end

endHere each translator module builds a uniform Repo struct. There, we have a clear place where the conversion from the client to the application should happen. That function should worry only about converting. If you end up needing more to be done, try to move small responsibilities elsewhere. Where? I’ll leave that to you, but I would start by moving responsibilities to the clients or a new module under the “hub” namespace. Try to keep the conversion functions as explicit and straightforward as possible.

Now, we need to update the SourceSuppliers to get repositories through all service clients through our standard interface:

# lib/central_source/source_suppliers/source_suppliers.ex

alias CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.{

BitPocket,

GitTab,

GitRub,

Repo

}

# …

@source_suppliers %{

bitpocket: BitPocket,

gittab: GitTab,

gitrub: GitRub

}

# …

def get_user_repos(user = %User{}) do

repos =

for {kind, username} <- user.configured_accounts do

module = @source_suppliers[kind]

case module.get_user_repos(username) do

{:ok, repos} -> repos

{:error, _reason} -> []

end

end

Enum.flatten(repos)

endHere we’re using the dynamic nature of Elixir to take configured user accounts, then determine which module to call during runtime, take all repositories from successful results, and flatten them into a single list. This implementation is naive, of course, isn’t warning about fetching errors. It’s assuming that we always have a module for a configured account, and it’s inefficient because it is bringing each service sequentially. But, to illustrate how a dispatcher works, it’s a good example. I’ll leave the optimisations and observability code up to the reader.

You should keep in mind that making the other levels of the application less aware of the specific types of service they are handling. Instead, they should be aware of their services capabilities. It can help you have fewer change codes when you start to add more and more providers. See some examples:

# prefer

case repo.favorites_count do

:unknown -> "unknown.png"

0 -> "zero.png"

_ -> "many.png"

end

# not preferred

cond do

repo.kind in [:bitpocket] -> "unknown.png"

repo.favorites_count == 0 -> "zero.png"

true -> "many.png"

end

# prefer

def can_open_pull_request?(%Repo{kind: kind}) do

module = @source_suppliers[kind]

function_exported?(module, :open_pull_request, 2)

end

if can_open_pull_request?(repo) do

# do a job

else

# return a error

end

# not preferred

if repo.kind in [:git_tab, :bit_pocket] do

# do a job

else

# return a error

end

# fair usage

def icon(repo), do: "#{repo.kind}.png"

# will return "bitpocket.png", "gittab.png", "gitrub.png"All this code is an implementation suggestion. Less other systems parts know about the details of each service provider, more flexibility you have to add or remove providers isolating failures and mitigating cascade changes.

Read with Elixir Protocols

So far, we covered how we can call and connect to external services. But, what happens when the external services want to send application notifications? Each service can send messages in different shapes, so we need to read them uniformly. Let’s see how Elixir protocols can help us!

Notification from an external service provider can come through many protocols, like HTTP, AMQP, gRPC, etc. At the protocol level, I don’t have many ideas on how to centralize that. I would keep the protocol parsing as a matter up to the reader. But if you want a suggestion, I would make it specific per service provider. The service provider can offer tools to solve the protocol. Let’s see an example:

# lib/central_source_web/controllers/gitrub/notification_controller.ex

defmodule CentralSourceWeb.GitRub.NotificationController do

use GitRub.NotificationController

@impl true

def handle_pull_request(%GitRub.PullRequestNotification{} = pull_request) do

CentralSource.notify_pull_request(pull_request)

end

endHere, the GitRub client library offers us a controller macro where we can put in our applications, and we only need to implement the callbacks. The callback gives us a handy struct, so the original notification format is hidden from us. This idea can sound like overkill, so go ahead and put the code of processing the service provider notifications on your web folder. I don’t think it’s wrong. The critical part here is, each service provider should generate a struct of their message. For example:

# lib/git_rub/pull_request_notfication.ex

defmodule GitRub.PullRequestNotficiation do

defstruct [:id, :author, :title, :description, :repo]

end

# lib/bit_pocket/merge_request_notification.ex

defmodule GitRub.MergeRequestNotification do

defstruct [:uuid, :creator, :description, :repository_id]

end

# lib/git_tab/pr_notfication.ex

defmodule GitRub.PRNotification do

defstruct [:sha, :author, :title, :summary, :repo_uid]

endAgain, here the recommendation is creating data structs that respect their service providers naming. Now, how can we make the data access through these structs uniform? Here comes Elixir Protocols.

While Elixir Behaviours are for modules, Elixir protocols are for data structs. It’s always good to think from the caller perspective. What kind of data the caller needs? Let’s do a draft implementation:

# lib/central_source/central_source.ex

defmodule CentralSource do

alias CentralSource.{Accounts, Notifier, SourceSuppliers}

def notify_pull_request(notification) do

with {:ok, repo} <- SourceSuppliers.get_repo(notification.provider, notification.repo_id),

{:ok, user} <- Accounts.get_user_by_username(notification.kind, repo.owner) do

Notifier.notify_pull_request(user, repo, notification.title, notification.author)

end

end

endHere, we need to know the service provider, the repository id, pull request’s title, and author from the caller’s perspective. Let’s create a protocol for that:

# lib/central_source/source_suppliers/pull_request_notification.ex

defprotocol CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.PullRequestNotification do

@doc "Returns the provider of the notification"

@spec provider(t) :: :atom

def provider

@doc "Returns the repository id which pull request was open"

@spec repo_id(t) :: String.t()

def repo_id

@doc "Returns the pull request's title"

@spec title(t) :: String.t()

def title

@doc "Returns the pull request's author username"

@spec author(t) :: String.t()

def author

endYeah, Elixir protocols are just a bunch of functions without their body. We will implement the function’s body in different modules. One module for each struct in the translation layer. That’s is how it looks:

# lib/central_source/source_suppliers/git_rub/pull_request_notification.ex

defimpl CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.PullRequestNotification,

for: GitRub.PullRequestNotification do

def provider(_pull_request), do: :gitrub

def repo_id(pull_request), do: pull_request.repo

def title(pull_request), do: pull_request.title

def author(pull_request), do: pull_request.author

end# lib/central_source/source_suppliers/bit_pocket/pull_request_notification.ex

defimpl CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.PullRequestNotification,

for: BitPocket.MergeRequestNotification do

def provider(_merge_request), do: :bitpocket

def repo_id(merge_request), do: merge_request.repository_id

def title(merge_request), do: String.slice(merge_request.description, 0..50)

def author(merge_request), do: merge_request.creator

end# lib/central_source/source_suppliers/git_tab/pull_request_notification.ex

defimpl CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.PullRequestNotification,

for: GitTab.PRNotification do

def provider(_pr), do: :gitab

def repo_id(pr), do: pr.repo_uid

def title(pr), do: pr.title

def author(pr), do: pr.author

endYou can see that we’re defining the same functions again, but this time, putting the conversion code in the function’s body. If you forget to implement any protocol function, Elixir will tell you that. Now, our central logic code can rely on the protocol functions. And the protocol will dispatch to the correct function depending on the struct. See:

# lib/central_source/central_source.ex

defmodule CentralSource do

alias CentralSource.{Accounts, Notifier, SourceSuppliers}

alias CentralSource.SourceSuppliers.PullRequestNotification

def notify_pull_request(notification) do

provider = PullRequestNotification.provider(notification)

repo_id = PullRequestNotification.repo_id(notification)

pr_title = PullRequestNotification.title(notification)

pr_author = PullRequestNotification.author(notification)

with {:ok, repo} <- SourceSuppliers.get_repo(provider, repo_id),

{:ok, user} <- Accounts.get_user_by_username(provider, repo.owner) do

Notifier.notify_pull_request(user, repo, pr_title, pr_author)

end

end

endUsing Elixir protocols to abstract the service client to build a reliable generic algorithm that doesn’t need to know what’s behind the scenes. You can put any code on these protocol functions, but I would avoid adding putting side effects. This protocol aims to offer a uniform way of reading the service clients specific structs. An impure function here can create lots of surprises for developers. For this case, if you need a function with side effects, I would move it to the “hub” module, the one that defines behaviours.

Wrapping up

The CentralSource example following the Aggregation of Services pattern the directory should look like something like this:

.

├── lib

│ ├── bit_pocket

│ ├── central_source

│ │ ├── central_source.ex

│ │ └── source_suppliers

│ │ ├── bit_pocket

│ │ │ ├── bit_pocket.ex

│ │ │ └── pull_request_notification.ex

│ │ ├── git_rub

│ │ │ ├── git_rub.ex

│ │ │ └── pull_request_notification.ex

│ │ ├── git_tab

│ │ │ ├── git_tab.ex

│ │ │ └── pull_request_notification.ex

│ │ └── source_suppliers.ex

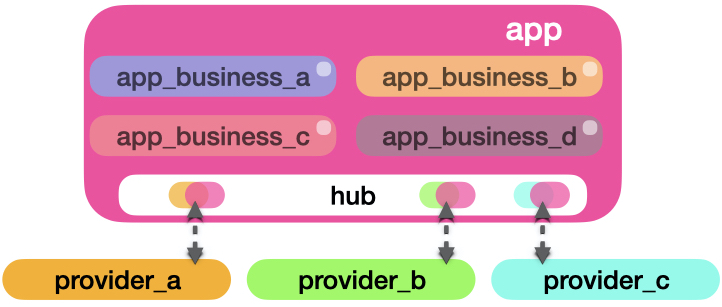

│ ├── git_rub

│ └── git_tabIn the lib folder, we have the service provider clients. Independent clients that don’t care what the application does. The application, central_source, depends on clients and has a “hub” mechanism in source_suppliers.ex module. In the source_suppliers folder, we implement Elixir behaviours for functions that call the clients and produce side effects. And, we have Elixir protocols implementations that help uniformly read provider clients structures. All that resonates with the AoS image from the beginning:

Wow! That was a long post! I saw this pattern emerging in a couple of forms. They were kind of similar, but this one that I presented to you, I liked the most. This pattern is not the fastest in terms of speed. Neither the one that you’ll write less code. What’s the good then? Here you have a clear boundary between the modules. And you have Elixir toolings that force you to write explicit interfaces. I found that it was useful for the maintainability and speed onboarding of people to write new integrations.

Should you follow it? I would say it depends. 😂 You don’t need to follow AoS by the book. Pick up the things that you like. Every team and company are different. This pattern was beneficial for me in the past but might not be for you. Use it as inspiration to build your own systems. Did you see other designs showing up in your applications? Tell me more about it in the comments.